Jonathan Landy

It's risky for a business to invest in new, unproven products. Yet, there are two strong forces pushing apparel businesses to invest heavily in new styles. In this post, we examine how these competing forces shape strategy across different apparel sectors and introduce a mathematical framework for rationally setting new style investment. By applying this model, businesses can make data-driven decisions that minimize risk while maintaining a dynamic and engaging assortment.

Interested in seeing how this might apply to your business? Read on, or reach out to discuss.

New styles: risk-reward tradeoff

New styles play a crucial role in the apparel industry for two reasons:

-

First, while proven styles generate steady revenue, each will eventually go out of fashion and need replacement. To ensure strong alternatives are available when that happens, brands must continuously explore new styles to identify future bestsellers.

-

Just as importantly, new styles keep returning customers engaged — without fresh options, repeat visitors lose interest and shop elsewhere.

With some thought, we can see that these considerations set precise minimum investment requirements for new buy - in general one or the other will be more strict, depending on the specifics of the business. In either case, some minimal level of new buy applies that is essential to keep the business thriving. Unfortunately, new styles also carry significant demand risk - unsuccessful ones contribute heavily to clearance costs. Managing this tradeoff to set the optimal amount of new style investment is a core challenge of apparel merchandising.

In the following section, we formalize these ideas mathematically, providing a framework to help businesses set their new buy exposure — a high-leverage decision. This in-depth analysis will be especially relevant for analysts within apparel businesses. If you'd like help applying these equations, feel free to reach out to VarietyIQ. After the heavy lifting, we illustrate the results with a numerical example and conclude with a discussion of qualitative takeaways for apparel strategy.

A Data-Driven Framework for Precision Buying

Optimal new buy equation

As outlined above, new buy products carry significantly more risk than rebuy, and so we’d like to carry as little new buy as possible. However, there are two counterforces that set minimum new buy investment – the need to have novel options for returning customers, and the need to identify replacement bestsellers as the old ones go out of style.

In practice, one of these effects will dominate for a given business. As a consequence - see the appendix for derivation - the optimal new buy fraction will be given by

We’ll walk through the significance of this equation just below, but first define the variables present. Here,

- new buy products carried per year

- total product count for the year

- typical rebuy order size divided by the minimum order quantity

- fraction of sales going to returning customers who demand new buy

- fraction of new buy styles deemed worthy of rebuy program status

- style lifetime - the average time till a product goes out of style

With these defined, we see that the left side of (1) gives the fraction of products that should be new buy, and the right of (1) relates to the two driving forces for new buy:

- The first gives the minimum fraction needed to keep returning customers who demand new buy satisfied.

- The second term is fraction needed to replenish prior best-sellers as they go out of style.

We take a max of these two to decide which dominates for a given business.

Behavior of the two terms

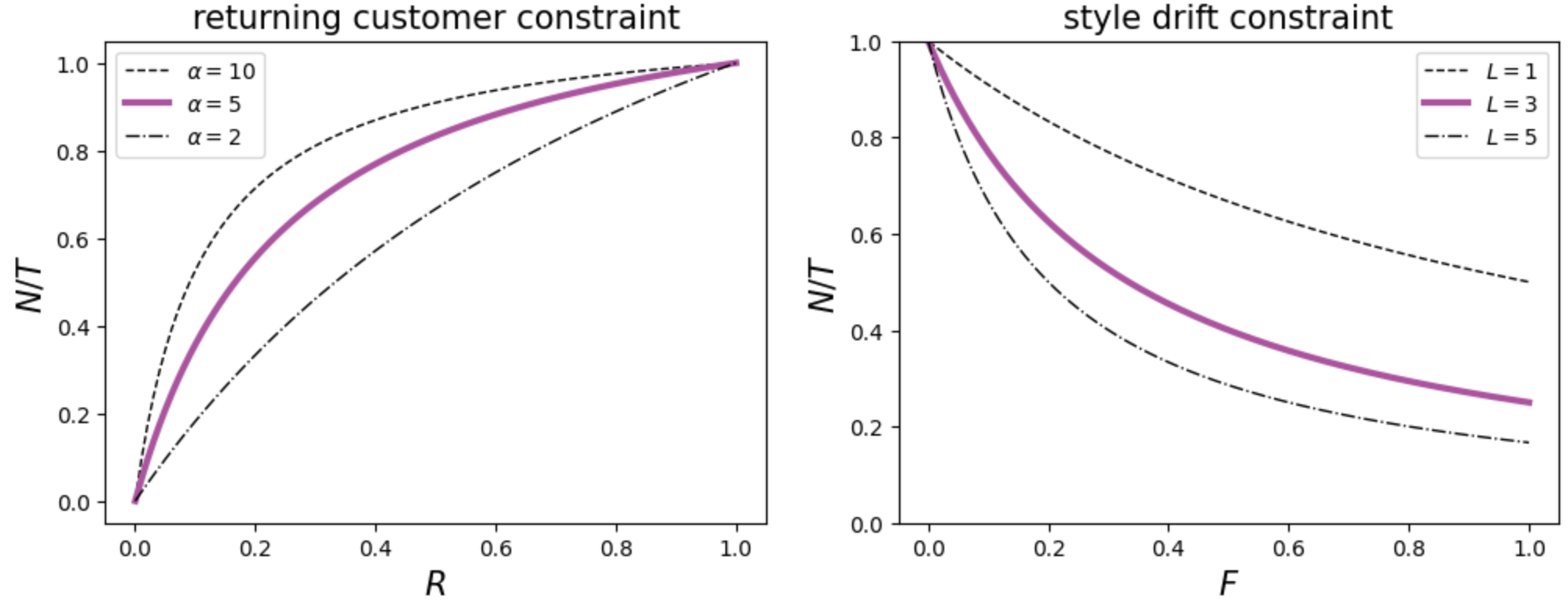

Plots of the two terms in (1) can be seen below.

The first plot at left shows the returning customer constraint as a function of - the fraction of demand that goes to new buy products. We plot this for three different values for the parameter . The main observations here are:

- We obviously need to buy more new buy if the demand for that increases as a fraction of the total demand (if increases),

- Further, if new products are purchased at the minimum order quantity, and this is a small fraction of the volume at which rebuy products are purchased, then we'll need to buy a large number of new buy products to meet the demand (as goes up, we need to buy into more new buy products to meet demand).

In the second plot at right, we show the new buy fraction needed to satisfy the style drift constraint. The main takeaways are:

-

If only a small fraction of new buy is worthy of rebuy, we need to explore more to find good replacements for past best sellers - this will require that we buy into more new buy options.

-

Further, if the style lifetime goes down, we'll be under more pressure to find new bestsellers as the old ones more quickly go out of style. This again will force us to invest more in new buy.

These ideas are intuitive - having them encoded formally allows for their precise investment implications to be explored.

Numerical Example

Here, we'll consider a business with the following parameters:

- , so that rebuy products are typically bought at 5x the volume of new buy.

- , returning customers demand that thirty percent of the inventory be new or they lose interest.

- , a new product can on average be brought back three more years before it needs to be retired.

- , only ten percent of new buy products tried end up having high enough demand to be promoted to rebuy.

Plugging into (1), the optimal new buy equation, we get

In this case, we see that the second, style drift constraint is stronger and so determines the optimal rebuy. An interesting implication is that the optimal new buy rate is locally insensitive to the returning customer demand - satisfying the style drift rate constraint, we have more than enough new buy to satisfy the returning customers as well, even if they increase their demand somewhat. However, one can show that if were to grow past , the returning customer constraint would then become "binding", and we'd then be sensitive to changes there.

Qualitative implications for business

The consumer perspective

Untested products carry inherent risk. To offset this, businesses with a high share of new buy must raise prices across their assortments. This may explain why high-end fashion, where styles change seasonally and rebuy is minimal, tends to be relatively expensive—especially for smaller boutique shops, where risk does not always average out. In contrast, basics like tees and underwear, which rely more on proven sellers, remain affordable.

Changing customer base

Consider a growing brand that initially thrived on a loyal fan base but recently expanded its acquisition channels, bringing in many new, less sticky customers. While the number of returning customers may rise, their proportion of total sales could shrink. If the stronger force for setting new buy is returning customer demand, the business can now shift investment toward bestsellers. However, if new buy is dictated by the need to replace fading bestsellers, no change is required.

Businesses with few returning customers

Some businesses, like wedding dress shops or tourist stores, rarely see repeat customers. For them, new buy is dictated by the pace of fashion drift rather than returning customer demand. Interestingly, categories with infrequent purchases—such as wedding dresses—seem to me to experience slower style evolution. This raises the question: Does frequent purchasing accelerate fashion cycles as repeat consumers seek novelty?

Differing trend time scale

Some apparel sectors move faster than others. Women’s fashion, for example, evolves more rapidly than men’s. In fast-moving categories - with low values - businesses must maintain high new buy levels regardless of customer retention.

Historically, fashion cycles were slower. Have advancements in manufacturing accelerated trend shifts? If so, further improvements in production speed may not stabilize demand but instead drive even faster trend turnover, continually pushing businesses to keep up.

Similarly, we've heard that fashions change relatively slowly within the eye glass sector. Could this be because people buy fewer pairs of glasses than they do tops or dresses?

Summary

Navigating the balance between new styles and proven bestsellers is a fundamental challenge in apparel merchandising. In this post, we explore how two key forces — returning customer demand and the need to replace fading bestsellers — dictate a brand’s optimal new buy exposure. We introduce a mathematical model that quantifies this tradeoff, providing a sensible framework for setting new buy investement. This sheds light on why high-end fashion demands a higher price point, how changes in customer acquisition impact assortment strategy, and why fashion cycles accelerate in some categories but remain slow in others. By understanding these dynamics, businesses can fine-tune their merchandising strategy to minimize risk while keeping their assortments fresh and engaging.

Appendix: Derivation of the new buy exposure equation

Returning customer limit

Here, we consider the case where the new buy fraction required is set by the returning customer requirement – returning customers who demand new buy. In this case, the ratio of this demand to its complement will be proportional to the ratio of new buy product count divided by the rebuy product count:

The fit parameter here is the ratio of the volume at which rebuy products are purchased to the minimum order quantity. If we divide the right side on top and bottom by , we get

The ratio is the fraction of products that are new. Solving for this gives

the left side of (1).

Fashion drift limit

Just after (1), we define the total number of products as well as the number of new buy products, . Let the non-new buy product count be given by .

The rebuy products are known winners. We’ve tried these in the past and found them to resonate strongly with our customer base. We’d like to continue to sell these and drive revenue with these. However, each year, some of these start to go out of style and must be retired. On average then,

We need to be able to replace these with acceptable new buys each year. Not every new buy is worthy of rebuy however. If we only want to keep the top fraction of these, the number we can replace must equal the number that go out style, giving

or

Using this and the fact that , we then get

or

the right side of (1).

Thanks to Luke Judson at Taylor Stitch for helpful discussions and for posing this question, to Callie Ryan and Greg Novak for feedback on an earlier version of this post, and to Jaireh Tecarro for her support in creating the visuals.