Jonathan Landy

Merchandisers often carry a single garment in multiple prints or colorways. This can lift net sales by appealing to different preferences, but beyond a certain point, new variants might simply compete with the others — lifting expense but not sales.

To understand where that tipping point lies, we’ll explore here two limiting cases. The results:

-

For products where customers usually buy just one version — like a dress with a distinct cut — best results are obtained when the individual prints do not compete, but instead appeal to complementary sets of customers. In this case, the ideal number of colorways can be guided by analyzing individual customer preferences. We give an example below.

-

For products where customers often buy multiple versions — like a men’s dress shirt — repeat business is often very important. In this case, the product line can be modeled as its own mini-business within a business, subject to both acquisition and retention goals. Having multiple products aimed at a given customer segment — often through new, seasonal styles — is then essential for retaining loyal customers.

TL;DR: There are two regimes — and very different advice applies in these two cases on when to add another variant.

Curious to see how this might apply to your product line? Reach out to discuss!Case 1: Single purchase products

To jump in, we'll first consider the situation of a product that customers are unlikely to purchase more than one variant of. This could be because one is simply enough (e.g., a special occasion dress), or because owning multiple versions might be socially awkward if noticed.

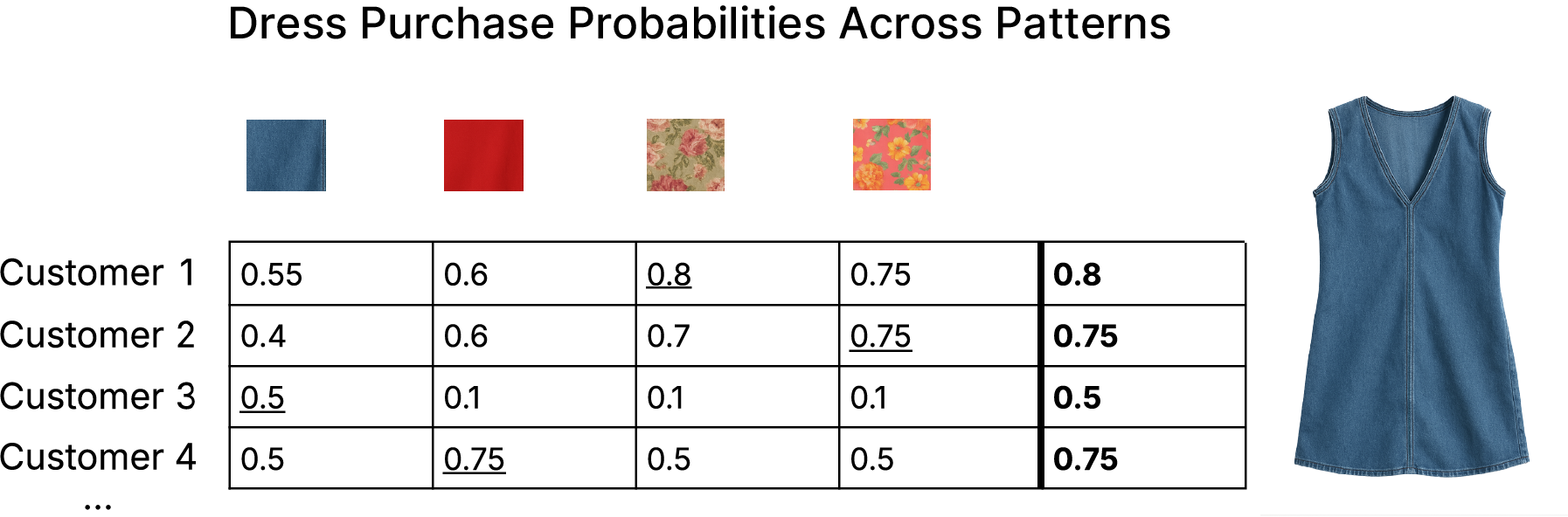

To illustrate the main ideas, we'll look at a case where we're considering multiple prints of a particular dress, as shown in the figure below. There, we see four prints along with purchase probabilities across these for a set of representative customers (Customers 1 through 4). These scores might come from customer surveys or from machine learning models trained to predict individual preferences.

A careful review of the table allows us to make the following observations:

- Since each customer will purchase at most one dress, we can treat the collection of dresses as a single "super product." The chance a customer makes a purchase is determined by her highest score across the prints — shown in the rightmost column. Expected net sales is the sum over rows in this column — we should strive to increase this.

- In this example, each print happens to be a top choice for at least one customer. If these customers are representative of the full set, this means that we can expect to see plenty of sales flow through each variant.

- However, the third and fourth prints (both florals) appeal to similar customers — Customers 1 and 2. If one of these prints were dropped, the other would still likely be chosen by both customers with little loss to overall sales (an expected drop of just 0.05 in either case). In other words, the two florals compete strongly with each other.

- In contrast, the solid blue and solid red variants are seen to appeal to separate customers (blue appeals to Customer 3, red to Customer 4). The customers who prefer these would be much less likely to purchase anything if their favored variant weren't available. For this reason, each of these is a good addition to the assortment.

The takeaway:

When dealing with a product that customers are unlikely to buy in multiples, each print should aim to serve a distinct audience. Otherwise, new colorways will fail to lift net sales meaningfully. To determine the optimal number of colorways, evaluate the expected lift in net sales from the next best addition and weigh this against the operational cost of introducing it. As long as the net benefit is positive, the addition will drive value.

Required methodology:

To estimate the lift in net sales from a new print, we must either (1) use our intuition, (2) run A/B tests to measure it directly, or (3) understand demand at the customer level — this last approach allows for quantitative accuracy without running a great many tests, and is the approach taken at VarietyIQ. In contrast, the more common product-level demand modeling methods fall short here — these can't capture cannibalization effects between similar variants, and so cannot identify the optimal colorway count.

Fig 1. Customer affinity scores (purchase probabilities) are shown across four print variants for a given dress. The top score for each client is bolded and shown in the right-most column. Because customers will purchase at most one option, these max scores set their purchase probabilities.

Case 2: Multiple-purchase products

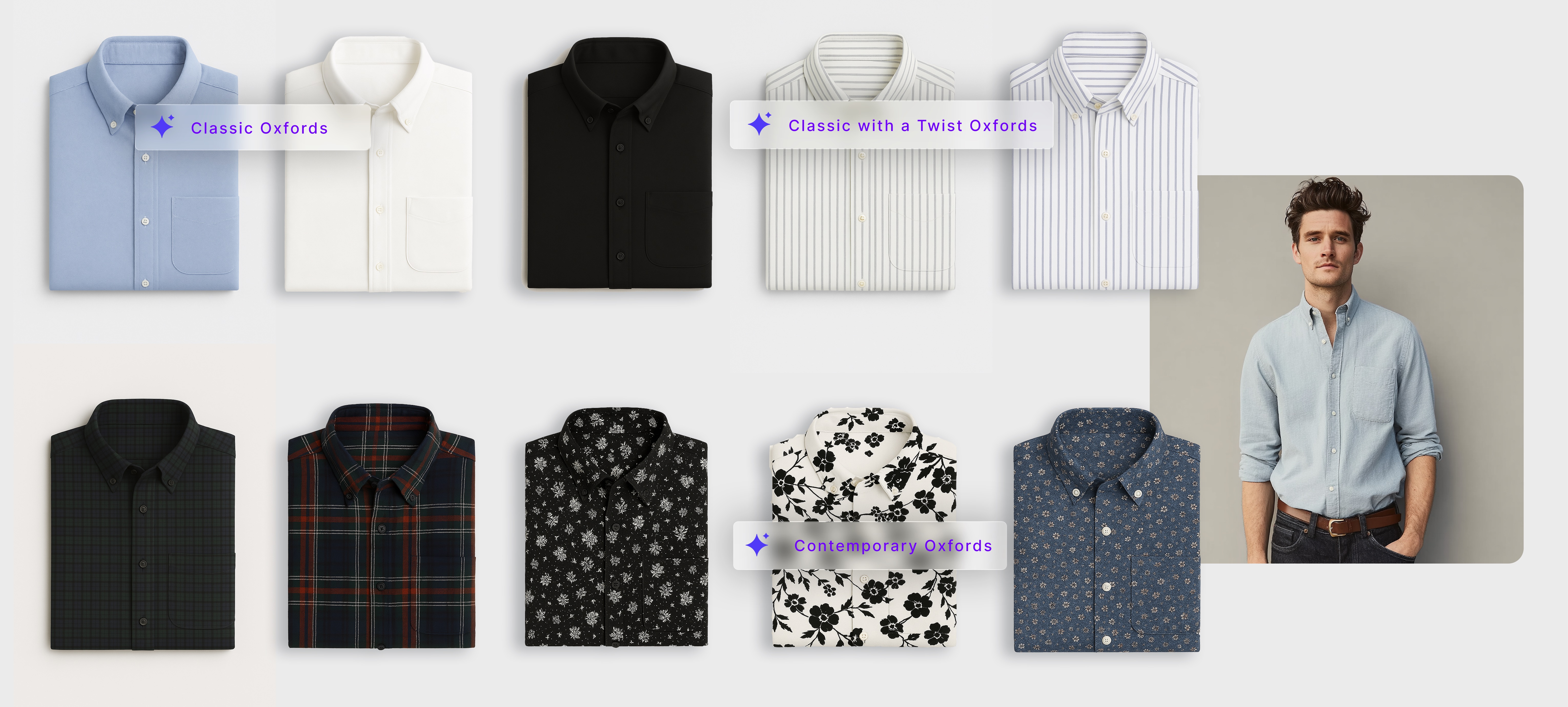

Next, we consider the case of a product line where customers are willing to purchase more than one variant. These are typically staple items with a consistent cut — think slacks, dress shirts, or tee shirts. To be specific, we’ll focus on men’s dress shirts, as shown in the figure below.

Interestingly, for products like this, we've found that repeat customers often drive a large fraction of demand. For a given seasonal print, upwards of 75% of sales may come from repeat purchasers. These are customers who already know they like the fit and feel of the product, and so are happy to return for repeat purchases — provided they can find a novel print to add to their wardrobe.

In this case, as noted above, it’s helpful to think of the product line as a mini-business within a business. The greatest-hit prints for the product should be carried as evergreen variants — not to retain existing customers (who have likely already seen them), but to attract new customers to the line. Alongside these, a portion of the assortment should be reserved for rotating seasonal prints. Unlike in the single-purchase case, these don’t need to each target different segments. In fact, we will likely want to carry multiple prints aimed at each relevant core demand segment in this case. Our customer-level demand modeling approach can identify which variants will continue to drive value within a segment. If a seasonal print performs particularly well, it can be promoted to evergreen status. But its primary role is to deliver novelty and reduce churn among returning buyers — many of whom may engage with your brand only through this product line.

So how do we set the right number of product variants in this case? And how should we divide the line between greatest hits and new options?

For the first question, we recommend applying standard merchandising logic — based on minimum order quantities, inventory cost, and expected demand. Ideally, each product program of the sort we're discussing here will not compete too strongly with other product categories, so external cannibalization can be ignored to first order.

As for the balance between new and evergreen variants, this is a very interesting topic in its own right! We refer you to our detailed post on this topic here, where we show that the answer depends on two key effects: the rate of style drift (how quickly customer tastes change), and the fraction of demand driven by repeat business. In general, one effect dominates and will determine the right fraction for a given product line.

The takeaway, methodology:

When dealing with a product that customers are happy to buy in multiples, it’s not only fine to offer multiple prints that appeal to the same segment — it’s strategic (however, it is important to always ensure an appropriate balance across segments — VarietyIQ's speciality!) This kind of product line should be treated as its own mini-business, complete with its own customer acquisition and retention strategy. Each season, carry a mix of evergreen hits to draw in new buyers and fresh prints to keep loyal customers engaged. Again, the optimal mix can be determined by applying our analysis here.

Fig 2. When customers are willing to buy more than one variant of a product (e.g., for dress shirts, as shown here), the assortment should have multiple options available for each segment. It should also contain a mix of evergreen bestsellers as well as seasonal new styles.

Summary

Determining the right number of variants for an apparel product line is a very common challenge — how many colorways are too many, and when does adding more actually drive value? The answer depends on whether customers tend to buy just one version or come back for more. For single-purchase products, each print should appeal to a different audience to avoid cannibalization. For products with high repeat purchase rates, like dress shirts or tees, this is not the case. However, we do still need to ensure we have the right balance of products aimed at each segment — both across styles and the mix of new vs evergreen bestsellers. By combining customer-level data with a structured framework, merchandisers can make more confident decisions — and build leaner, more effective product lines.

Thanks to Jaireh Tecarro for creating the visuals for this post.