Jonathan Landy

Brands often sell through both the direct-to-consumer (DTC) and wholesale channels, with demand in each uncertain before the season starts. Wholesale orders happen first at a lower price, and whatever inventory remains goes to DTC. This introduces a key gamble: Should we always accept a wholesale order if it comes in now, or should we reserve some pre-determined amount of inventory for DTC, where the margin is higher but sales are not guaranteed? In this post, we outline a simple rule for making that tradeoff and show that it can meaningfully increase net revenue across channels.

Wholesale process and key results

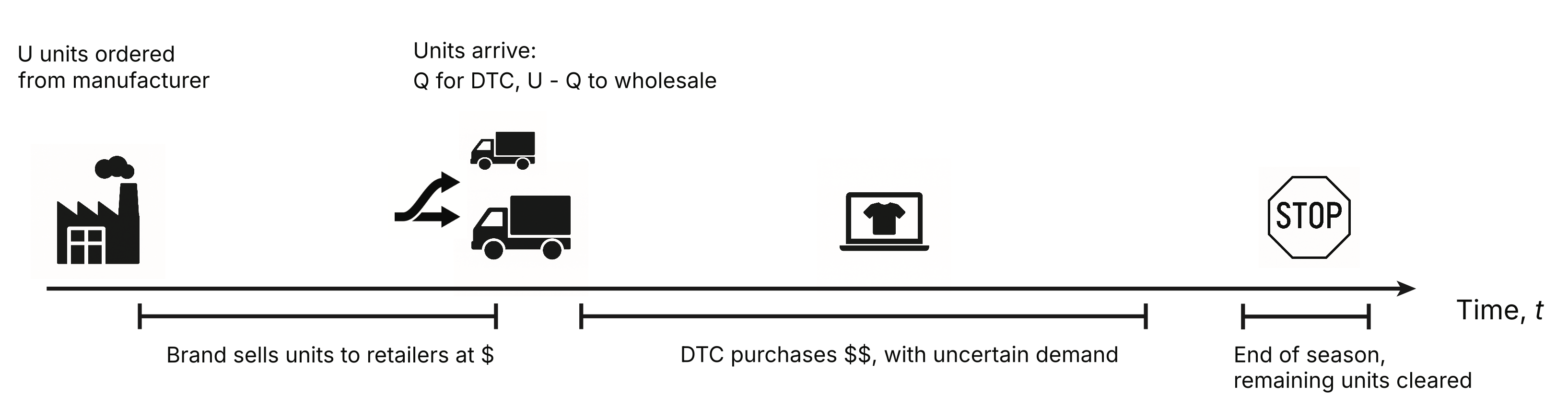

Each season, a brand develops its line and places production orders, locking in quantities. While production is underway, the line is sold to retailers at the wholesale price — typically one-third to one-half of the DTC price. This creates a familiar tradeoff: take the guaranteed wholesale sale now, or reserve units for potentially higher-margin DTC sales later, risking clearance costs if demand falls short. Figure 1 below summarizes the timeline of this process.

In Appendix A, we show that the optimal DTC reserve quantity satsifies:

The left side here represents the probability that all reserved units sell through DTC; the right side is the wholesale-to-DTC price ratio. We should choose so that these two are equal.

To build intuition:

- When wholesale prices are much lower, DTC sales are far more valuable. In this case, (1) states that we should reserve units up to the point where a DTC stockout becomes unlikely.

- On the other hand, if wholesale and DTC prices are equal, there’s no reason to hold back inventory for DTC. In this case, (1) says that the probability of DTC stockout should be at the optimal reserve quantity, which implies . In other words, we shouldn't reserve inventory for DTC in this limit: If wholesale buyers offer the full price, we should take the sale.

The next section shows how to compute the optimal reserve quantity for more general price ratios.

Figure 1: Timeline of the process. After the brand orders units from the manufacturer, it sells some pre-season to retailers at a lower wholesale price. Once shipments arrive, inventory is distributed to both DTC locations and wholesale partners. Units held for DTC sell at higher margins. But if we reserve too many units, we might incur significant clearance costs.

Practical Examples

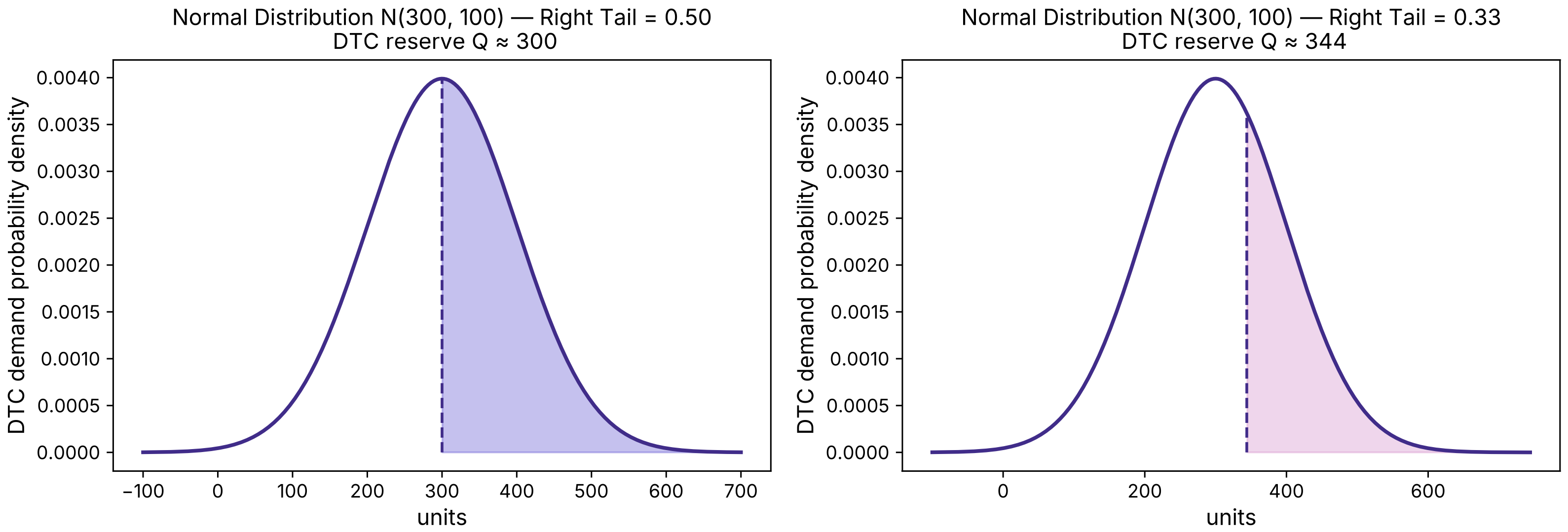

In the following examples, we’ll consider a shirt with an average realized DTC price of $100. We assume DTC demand follows a normal distribution with mean 300 and standard deviation 100:

This means that before the season begins, our best estimate of DTC demand is 300 units, though actual demand could be higher or lower. In particular, there’s about a 65% chance it will fall between 200 and 400 units (). The standard deviation can be estimated empirically by comparing past demand outcomes to original forecasts.

We’ll now use (1) to see how the optimal number of units to reserve for DTC changes with the wholesale price.

Case 1: Wholesale price is half retail price

Suppose the wholesale price of our shirt is $50 — half the DTC price. Plugging this into (1), we want the value of Q that satisfies:

For a normal distribution, the point where stockouts occur half the time is the mean of the demand distribution — this is shown in the left panel of Figure 2 below. This means that in this case, we should reserve units for DTC.

Case 2: Wholesale price is one-third retail price

Optimal Reserve Quantity

Now suppose the shirt is offered to wholesalers at a steeper discount — $33, or one-third the DTC price. Plugging this into (1) gives:

As shown in the right panel of Figure 2, this corresponds to units — greater than the expected DTC demand of . In other words, even if a wholesale account wanted to purchase those extra units before the season, it’s better on average to reserve them for DTC, where the margin is much higher. More generally, as the DTC prices rises relative to wholesale, we'll want to reserve more units for the DTC channel.

Revenue Benefit

How much additional revenue do we expect when we hold exactly units for DTC rather than the expected demand of ? As shown in Appendix B, the expected net revenue gain is approximately:

To put this in context, suppose we originally produced units at an average unit cost of , for a total manufacturing cost of:

The incremental margin improvement is then

quite sizable! In fact, this translates to more than a 5% increase in total margin, achieved simply by optimizing the mix between wholesale and DTC availability.

Figure 2: Demand for our example shirt follows a normal distribution with mean 300 and standard deviation 100. (Left): When the wholesale price is half the DTC price, the optimal reserve is , where DTC stocks out half the time. (Right): When the wholesale price is one-third of DTC, the optimal reserve rises to about , since higher DTC margins justify holding more inventory for potential DTC demand.

Summary

When a product sells through both wholesale and DTC channels, optimal inventory management requires that we hold back DTC units only until the expected revenue of doing so no longer outweighs the certainty of a wholesale sale. Finding that balance requires that we consider the odds of DTC sell-through at the reserved inventory quantity.

Our examples highlight a clear rule of thumb: The higher the DTC price relative to wholesale, the more inventory a brand should reserve for DTC. As the margin gap between channels widens, it becomes increasingly worthwhile to take some risk on DTC demand rather than securing lower-margin wholesale revenue early. In practice, this optimization can deliver a sizable uplift in total margin — 5% in our second example — without requiring a change to overall buy quantities or pricing.

Appendix A: Derivation of (1)

Consider whether it makes sense to reserve the -th unit for DTC. The expected revenue lift from doing so is

For the first few units, the probability of DTC sell-through is high, so this expected value is close to the full DTC price. But for later units — say, the thousandth — the likelihood of selling through declines, and the expected revenue lift (8) becomes only a small fraction of that price.

When we have the option to sell a unit at the wholesale price, we should decline that sale only if the expected DTC revenue exceeds the wholesale revenue we give up. The point of indifference occurs where the two are equal,

Rearranging gives (1).

Appendix B:

Here, we consider the expected revenue benefit of the optimal units DTC reservation in our second example above, relative to simply reserving the expected unit DTC demand.

First, suppose a retailer had asked to purchase these extra units and we let them take them. In this case, we'd enjoy

On the other hand, expected revenue from DTC if we have units is

A quick calculation shows this is .

Had we instead only reserved units, the expected DTC revenue would have been

Here, we get .

The net expected revenue increase is this extra DTC component minus the forgone wholesale revenue,

the value we quoted in (5) above.

About VarietyIQ

VarietyIQ helps retailers and brands optimize inventory decisions — from forecasting and allocation to pricing and product mix. We combine advanced data science with deep retail expertise to improve efficiency, profitability, and growth.

Need help optimizing allocation across your channels? Get in touch — we’d love to connect.

Thanks to Jaireh Tecarro for creating the banner image for this post, and to Luke Judson and Grant Rhodes at Taylor Stitch for helpful discussions relating to this work.