Jonathan Landy

We review the classical framework for profit-maximizing pricing under steady demand. Here, demand elasticity is the key quantity governing price sensitivity, and we show how it can be estimated from historical data. Once elasticity is known, retailers can plug it directly into the profit-maximizing pricing formulas: one for setting prices before a selling period, and another for adjusting prices in-season to clear inventory.

Demand Elasticity

A key measure in pricing theory is the so-called elasticity of demand, defined as follows

Here, is the unit demand at price , and is the change in demand as the price changes by a small amount . The elasticity for a product tells us whether an change in its price results in more or less than an change in demand.

E.g., if we decrease the price by and demand increases proportionally by , we get elasticity

But if demand only goes up by , then the elasticity is

Similarly, if we decrease the price by and demand goes up by even more, say , then we get

We can say that when the elasticity is larger than , the demand responds "super-linearly" to changes in price. Empirical evidence suggests this is what happens in most scenarios. We’ll see that’s important in our price optimization analysis below.

Constant elasticity model

A simple model that is convenient for both theoretical and practical applications is the so-called "constant elasticity" model. This asserts

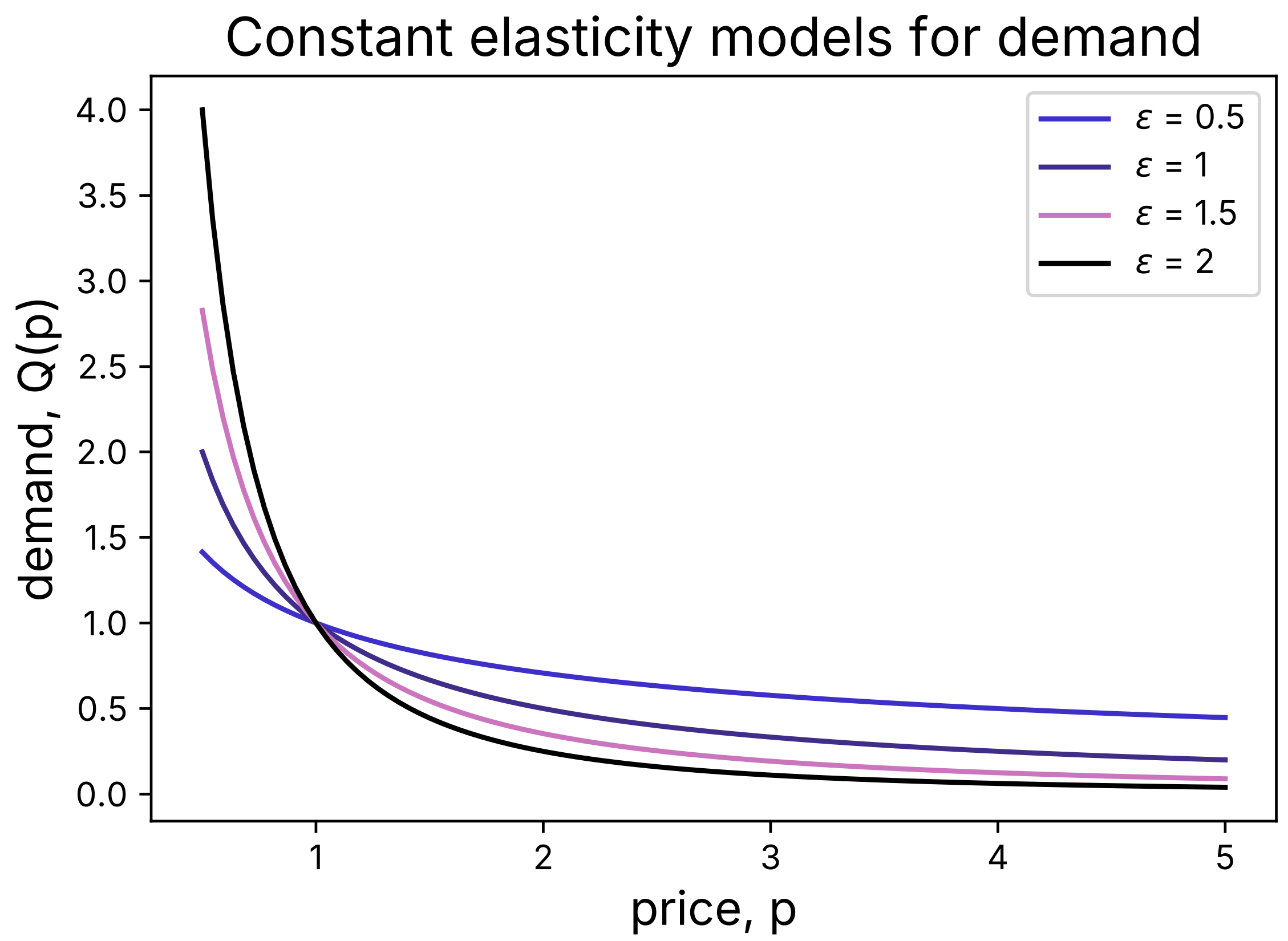

where and are parameters. The former controls the scale of demand and the elasticity. Figure 1 below plots this for a few different values of .

To see that controls the elasticity of model (5), we differentiate :

To get the elasticity, we now divide by

This gives

This shows that is in fact exactly equal to the demand elasticity in this model. It's a constant, independent of price.

In practice, elasticity is rarely constant over all possible price ranges. However, when considering only modest changes in price, elasticity can often be treated as locally constant. For that reason, using (5) to model practical situations will frequently work well, much as a Taylor series expansion can provide a good local approximation to a general curve. Indeed, (5) can be viewed as arising from a low-order expansion: Taking the log of that equation gives

This form allows us to interpret the constant elasticity model as a linear approximation to whatever the true relationship is between and . One way to fit the model to historical data then is via a simple linear regression in log space. We will stick to this level of approximation here, but note that higher-order expansions can be used to capture changes in elasticity over wider price ranges.

Figure 1: The constant elasticity model (5) is plotted at various values of (here, with in each case). We can see that the high elasticity models show strong price sensitivity — rising quickly at low prices and dropping more quickly at higher prices. Empirics suggest elasticity is typically larger than .

Pre-Period: Maximizing Profit Analysis

Let’s now consider the situation where we intend to purchase some inventory at an average unit cost and want to find the price that will maximize our net profit over the period. We assume we know the demand curve parameters and ahead of time. At a given , the net profit we expect to enjoy is then

To maximize this, we differentiate with respect to and set this to zero. This gives the equation

Solving for gives

This is the classical “markup rule”: The factor sets the optimal retail price markup over unit cost. Notice that this depends only on , and that as approaches from above the markup diverges. Intuitively, as elasticity decreases — meaning demand becomes less sensitive to price — it becomes increasingly favorable to raise prices, trading unit volume for higher revenue per unit. Fortunately for consumers, we typically find (see above), and this divergence is avoided in practice.

Plugging price (12) into (5) gives the quantity that should be ordered ahead of the period in order to meet demand at the optimal price point.

In-Period: Clearance vs. Margin Analysis

Now, let’s consider the situation where you’ve already purchased some inventory and have units remaining. You’ve already spent some time selling the product and now realize that your pre-period assumptions for demand are not quite right. Given available data, you now want to adjust the price so as to maximize the revenue you can capture from this inventory before the period is over. Finally, assume that all units that don’t sell can be cleared, allowing you to recoup a salvage value per unit not sold.

To optimize your outcome, you now want to maximize

What this means is that we should first check the price that maximizes net revenue over salvage, ignoring inventory constraints. If this results in fewer units selling than is available, great. However, if this requires selling more than is available, we instead pin the price at the value that just clears the available inventory.

In the first scenario above, the optimization is analogous to that in the prior section and we get

On the other hand, if we need to clear the inventory, the required price satisfies

Solving gives

Note that (16) is the first "optimal" price we've seen that depends on the product's demand scale parameter .

We need to choose the larger of the two prices (14) and (16). If this is the former, we can maximize revenue over salvage in an unconstrained way. If the latter, we are inventory constrained and so must pin the price at that value that will just allow us to clear the available remaining inventory. In this case, the price increases with the scale of demand, set by , and decreases with available inventory : We need to decrease the price more as we become more overstocked relative to demand.

Equating (14) and (16) provides an equation setting the decision boundary. We see that it depends on all the parameters present — , , and .

Summary and Practical Applications

In practice, pricing data for individual products is often limited. In these cases, retailers typically assume a common demand elasticity across all products within a category. Once this elasticity is estimated, both the markup and the initial price can be set using (12). Notably, this price does not depend on each product’s individual demand scale, but only on the shared elasticity parameter. If the products in the category have the same unit costs, they should then each be priced identically, but with order quantities determined by their individual demand scale parameters via (5).

Once in season and realized sales can be recorded, the scale of demand for each product will be more exactly determined. After a month of sales, say, those products determined to be at risk of not selling through at the initial price can be discounted. The discount price can be set using (14) or (16) above, whichever is larger. A complicating factor here is that customers often have a different sensitivity to the "full retail price" vs prices that are marked as discounts. In practice then, we may need to fit the dependence for both separately. A further complicating concern is that many retailers wish to maintain a premium image, and so are unwilling to set very steep discounts. In this case, if the clearing price is below allowable values, salvage may be the best option.

About VarietyIQ

VarietyIQ helps retailers and brands optimize inventory decisions — from forecasting and allocation to pricing and product mix. We combine advanced data science with deep retail expertise to improve efficiency, profitability, and growth.

Need help setting optimal prices for your business? Get in touch — we’d love to connect.

Thanks to Jaireh Tecarro for creating the header image for this post.