Jonathan Landy

Forecast error leads to misallocation of inventory across demand channels, driving lost sales. For example, for a product with units of demand split across two channels, we find that relying on a single prior sales cycle to guide allocation leads to a loss of roughly of potential sales.

In general, we find that misallocation losses scale as

In practice, this means misallocation matters most for lower-volume products and for assortments spread across many locations.

Combining our worked example with this scaling law provides a quick way to estimate misallocation losses for general products. While these losses can be meaningful, they fall sharply with improved forecasting, for example via data pooling across related products.

Misallocation and Avoidable Loss

The mathematics of allocation applies whenever a fixed supply must be divided across independent demand channels. Two common applications include the distribution of units across retail locations and the setting of size breaks for a garment.

The goal in allocation is to avoid scenarios where some channels are systematically over-resourced – and so unlikely to sell through their units, while others are systematically under-resourced – and so likely to stock out early, resulting in missed sales. In a situation like this, shifting units around to improve balance will lift expected net sales. In fact, we showed in a prior post that to maximize net unit sales, we must allocate units so that each channel has the same probability of stocking out.

To implement this optimal strategy, we must first be able to accurately forecast the demand distribution of each channel (i.e., how likely it is that demand will come in at each possible value for that channel). If our forecasts are inaccurate, supply will again be imbalanced. In the appendix to this post, we work out the following approximation for the misallocation loss that then results,

Here,

- The parameter characterizes the degree of error in the forecasts informing our allocation. In particular, if forecasts are based on independent prior sales cycles for the product, then Improving forecasts — e.g., by pooling data across similar products — reduces and thereby lowers misallocation losses. Conversely, ignoring available data drives higher, increasing losses.

- is the number of channels over which the product must be allocated. (For the derivation of (1), we assume the channels are of roughly similar scale – see the appendix for a generalization that does not require this.)

- is the total demand for the product. The fractional error (1) goes down with this because statistical error is lower for higher volume products.

Equation (1) the main result of our post. This provides accurate numerical estimates for losses that are not too large, and it also generally provides useful intuition for understanding how misallocation losses scale. E.g., from this we can see how the fractional loss increases as we cut demand across an increasing number of channels.

In the next section, we apply the result (1) to a concrete example. The following summary section then reviews some qualitative takeaways and also illustrates how to use the scaling rule and our one worked example to estimate general losses.

Example Application

To get a feel for (1), suppose we have a product with a total demand of units split across retail locations. Assume true demand is split 50-50 across the two locations, but we only have one prior noisy measurement of demand at each (this implies – see the appendix for details).

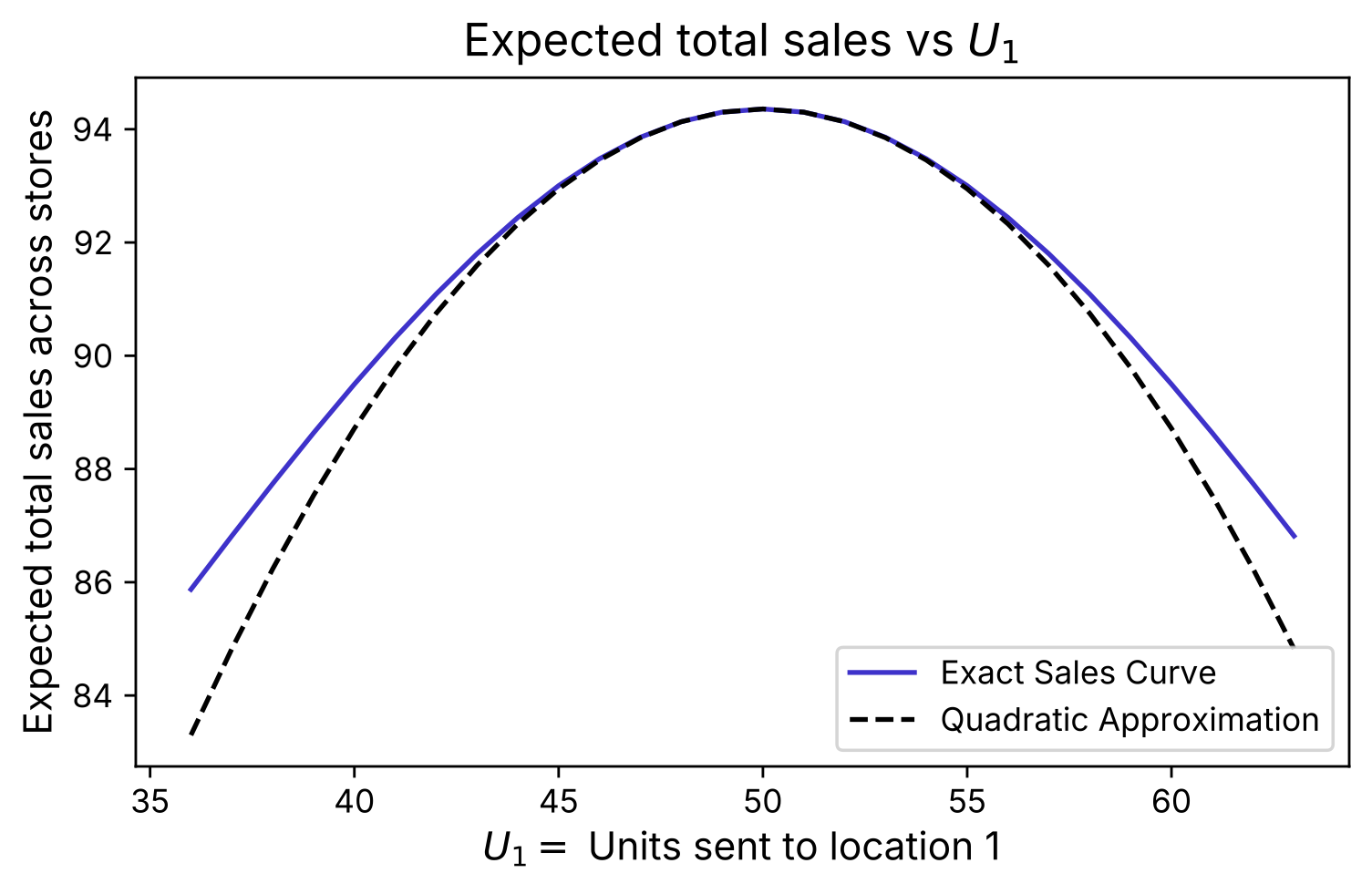

Suppose we purchase units for a second cycle and plan to allocate them across locations in proportion to the prior noisy measurements. If the first cycle comes in unusually strong at Location 1, we will overestimate demand there and send more than 50% of units in the next cycle. This will result in an imbalance, decreasing expected net sales. Indeed, in Figure 1, the blue curve shows the numerically evaluated net expected sales as a function of the number of units sent to the first location. There we see that expected sales are maximized at the balanced 50–50 split, where we achieve about 94 units of expected sell-through. We do not reach units because demand may come in soft at either location, leading to partial sell-through. Moving away from the balanced allocation reduces expected sales further.

Next, consider averaging over all possible outcomes from the first sales cycle. This will give us a sense of the typical loss that results from forecast error. To evaluate the average loss due to this sort of demand measurement error, we could average the values on the numerical blue curve, averaging over the demand measurement error distribution. However, it turns out we can also approximate the blue curve using a convenient analytic expression – the black dashed curve below. If we use this “quadratic” approximation and carry out the average, the result is (1) – again, see appendix for derivation. Plugging the values for our example into (1) gives us the estimated expected loss from misallocation:

That is, misallocation driven by measurement error reduces expected sales by about . In absolute terms, we expect to sell around units on average rather than .

Figure 1: Expected sales for a product with units of demand split evenly across two channels, shown as a function of the allocation . The blue curve gives the exact evaluation, and the dashed curve shows the quadratic approximation used in (1). Even with truly balanced demand, limited historical data can lead us to over-allocate to one channel – for example, sending more than units to Location 1 if it happened to run hot last time – reducing expected net sales.

Discussion

Our central result (1) shows that misallocation losses follow a simple scaling rule. Combined with the worked example above, this gives a simple way to estimate losses for general products. In particular, whenever forecasts are based on a single past sale period's data for the product, we have

For example, if we increase by (i.e., go from to ), the fractional loss will , going from to . Similarly, if we can double the amount data informing our forecasts, our value and expected net loss will both be cut in half.

Formula (1) applies when our total unit investment is close to the expected total demand. The more general expression (8) in the appendix shows that misallocation losses diminish outside this regime. If we greatly overbuy, no channel is likely to stock out; if we greatly underbuy, all channels will. In either case, reallocation details have little effect. This suggests a practical planning hierarchy: get total demand right first, and focus on allocation accuracy only once net supply and demand are reasonably aligned.

A second lever is forecast quality. If we double the amount of data informing our forecasts (for example, by pooling data across similar products), our forecast error parameter — and the resulting misallocation loss — will fall by half. Improving forecasts in this way can meaningfully reduce avoidable losses, often without increasing operational burden or requiring additional unit investment.

Appendix: Mathematical Derivations

In our first post on allocation, we derived the following

This says that the lift in expected sales for a given channel on adding one more unit there is equal to the sell through probability.

If we differentiate (4), we get

Here, is the pdf of the demand distribution of channel .

Now consider what happens when we attempt to optimize units across channels. At the optimal point , all values of (4) are equal. Suppose we move away from that and set

Assuming we are not far from the optimal solution, the change in sales at channel will be

Summing over all channels, we get

Here, we’ve used the fact that the first partials are all equal at the optimal point, and that the sum to zero. We’ve also used (5) for the second partial.

Equation (8) is a useful result that generalizes (1) above. It gives us an expression for the expected sales loss as we move away from the optimal solution for general (accurate, provided these are not too large – e.g., we used this formula to get the black dashed curve in Figure 1). Notice that this equation implies that the costs of misallocation are largest when the are maximized. This will occur when net supply is close to the net expected demand. As we move away from that limit, allocation concerns are less important. See the Discussion section for additional commentary.

To gain more intuition for typical scenarios, we now posit a Poisson-Normal distribution for the demand at a given site. With this, we have

If we plug into the normal distribution, we get

Now suppose that we are trying to send the expected demand to each site. Suppose no bias but that prior demand estimates follow from samples taken from the distribution (10). In this case, our estimate for will be noisy, and the expected of the next send will have value

with a common value across channels. Notice that if we have only one prior sample, then will be one here – a value we quote in the body of the post.

With these assumptions, the average cost in (7) will then go like

This again is a slight generalization of (1), one where we do not assume each channel is equal in size. To get to (1), we posit equal in size. Plugging this into (12) and dividing by the total demand, we get

which is equivalent to (1). We take these particular assumptions in order to highlight the fractional loss’s dependence on the number of channels.

About VarietyIQ

VarietyIQ helps retailers and brands optimize inventory decisions — from forecasting and allocation to pricing and product mix. We combine advanced data science with deep retail expertise to improve efficiency, profitability, and growth.

Misallocation costs a concern at your business? Get in touch — we’d love to connect.

Thanks to Jaireh Tecarro for creating the header image for this post.